The importance of sidewalks and a call for a manifesto or bill of rights for pedestrians. I wanted to avoid the word ‘pedestrian’ for its obvious pedestrian connotation. But, I also did not want to marginalise the pedestrian who has historical rights to entire roads to a mere sidewalk by using the word ‘sidewalker.’ So, I use both interchangeably.

‘Think of a city, and what comes to mind? Its streets. If a city’s streets look interesting, the city looks interesting; if they look dull, the city looks dull.’ – Jane Jacobs

“When people say that a city, or a part of it, is dangerous or is a jungle, what they mean primarily is that they do not feel safe on the sidewalks.” – Jane Jacobs

“I will [tell] the story as I go along of small cities no less than of great. Most of those which were great once are small today; and those which in my own lifetime have grown to greatness, were small enough in the old days.” – Herodotus

Introduction

As I wrote in a related post, I narrowly escaped from two road accidents, one as a pedestrian and the other as a biker. By the time you read this post, two people would have died in India in a traffic accident. That could be an underestimate. The WHO estimates one death every 25 seconds across the world.

In 2005, after delivering a talk on operational risk at a GARP Conference in Hong Kong, I was accosted by an elderly person, an expert on fatality. I forget his name. He shared insight on ‘near miss’ events which I referred to in my presentation. According to him, there were 30 critical events for every fatality and 30 ‘near miss’ events for every critical event. Information on ‘near miss’ events is rarely captured though they are critical to risk management and planning preventive controls. This applies equally to traffic management and preventing financial fraud.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) 2021 reported 155,622 fatalities, the highest since 2014. Nearly 70 thousand of these were due to two-wheelers. About 450,000 accidents occur in India annually, of which 150,000 people die. “India has the highest number of casualties in road accidents,” said the report. “There are 53 road accidents in the country every hour and one death every four minutes.”

Most of these accident fatalities involve two-wheelers and also pedestrians. A 2008 study by the University of Michigan and IIT Delhi put the share of pedestrians and two-wheelers, including motorised ones, at 60 to 90 per cent of fatalities across various Indian cities. Newspaper reports put the share of pedestrian deaths from 30 per cent to anywhere over 50 per cent. There are variations across countries across years and within a year. But, the woes of a pedestrian are not limited to fatalities.

A pedestrian’s woes

The footpath in India is called a pavement in most Commonwealth countries. The Americans and most literature on urban design prefer to call them sidewalks. To me, a sidewalk is more than just a footpath, as I will elaborate on. But I will use them interchangeably depending on the context.

Missing footpaths

Research shows that accidents and casualties are significantly lower on roads with footpaths than those without them. But, most roads in the heart of Trivandrum, barring a few exceptions, have retained their original width from a few decades back. Not designed for pedestrians, many roads have no footpath. Even if there are, many are drainage covers. With the city’s undulating terrain, these have their ups and downs and gaps that must be guarded against lest your mobile phone slips in between.

Mount Road, or Anna Salai, is Chennai’s best-known road. Its history goes back centuries as the road leading from Fort St. George to St Thomas Mount. Recently I found a stretch in Teynampet, where the ruling party has its head office, with no pavement (see images below). The hapless pedestrian is left to fend for herself, battling with mindless motorists.

Another image below is from the elite surroundings of T. Nagar in Chennai, where the footpath is well paved, but an old tree and other obstructions block the passage, and nobody can use the pavement.

See the image alongside from Kowdiar Avenue, Trivandrum’s best-known road. Some of these are too narrow or have obstructions of various types, including tree pits, to be even called a footpath.

Trivandrum

T. Nagar, Chennai

Encroached footpaths

Mumbai and Chennai also have their woes. I gave up on my first attempt walking from my office in Bombay Central to Churchgate, near where I used to live. Long stretches of the footpath had building material dumped on them. Near Marine Lines, a makeshift police station blocked the entire footpath. Double-storied hutments on footpaths cannot be shifted for sentimental reasons. Charles Correa, the distinguished architect, wrote that encroachers in Dharavi were leveraging the advantage of living on the cusp of three major railways, the main arteries of Mumbai.

Other obstructions include unauthorised places of worship, kiosks, vendors, hanging wires and huge electric boxes, uncollected debris, building material, and uncollected human or animal waste. Some well-meaning citizens are determined to green their city. They nurture gardens on public roads at the pedestrian’s expense, fencing off parts of the footpath.

In New Delhi, the footpaths in major colonies have been taken over by the cars of families whose houses cannot accommodate more than two cars. With every family member now owning a car in Vasant Vihar or Safdarjung Enclave, or any upmarket residential colony, a pedestrian is not safe walking on the roads. The situation is no different in most other cities.

A study by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) listed the following obstructions/encroachments: “Garbage heaps, dumping of construction materials, potholes, open sewers, slum proliferation, open urinals and defecations, transformers and police kiosks, extended encroachment of shop owners and hawkers have decimated the pedestrian environment.” (CSE, 2009)

Nearly in all sites pedestrians are being forced to walk in total modal conflict with motorized traffic increasing risk of accidents. … high modal conflict due to inaccessible sidewalks and discontinuous footpaths and also the motorists do not yield to pedestrians.

CSE, Footfalls: Obstacle course to livable cities, 2009.

Two-wheeler menace

The concrete bollards fixed on most roads, as in the T. Nagar pedestrian plaza, are intended to keep motorised vehicles out. But these usually leave wider gaps at places for wheelchair-bound or pram-pushing mothers. Two- and three-wheelers routinely misuse them, as do four-wheeled garbage vans (see images below). There was even the odd case of a biker desperately scrambling to get ahead through the footpath as if he were fleeing from the scene of a crime.

Imagine your shock when you are least expecting such a vehicle on the pedestrian pathway, honking from behind to express annoyance that you are in the way. But they can also come from the front at high speed, flashing lights asking you to give way. For pedestrian safety, it seems best not to declare them pedestrian-only pathways so pedestrians will be more careful.

A variant of this, to which even four-wheel drivers are increasingly culpable, is the practice of driving on the wrong side. Years of policing neglect have bestowed a certain perceived legitimacy to this. How can any civilized community put up with such despicable and dangerous behaviour?

Official apathy

Official apathy is not limited to uncleared debris or electric switchboards thoughtlessly positioned in the middle of footpaths. There are also bus stops where the waiting shelters take over pedestrian space. The apathy also extends to not having speed breakers where needed, say, near schools and hospitals, minor road intersections, sharp curves, down a gradient, before junctions or zebra crossings, or wherever vehicles can pose a danger to pedestrians. It is also responsible for open manholes, which can swallow unsuspecting public when the roads are crowded. An old family friend walking on a footpath fell waist-deep into one in central Kochi. Luckily for him, the pothole was just outside the city’s leading readymade retailer. He walked in (they allowed him) and came out in a new set of clothing.

Fellow pedestrian contribution

The pedestrian woes also come in no small measure from fellow citizens in different ways. Apart from those who encroach on footpaths by parking their vehicles, some walk untrained dogs, use pedestrian space to practice yoga and sell various wares. Some others decide that the world should listen to whatever music they like.

Connectivity

An essential part of a pleasing pedestrian experience is to have seamless connections across footpaths. Before zebra crossings became popular, jaywalking must have been very common, explaining how the absent-minded Pierre Curie, the Nobel Laureate, fell under the wheel of a carriage, cracking his skull.

It is the norm in most western countries for the motorist to stop when a pedestrian is about to cross, and not necessarily only at zebra crossings. This has as much to do with the law and stiff court sentences if convicted for overrunning a pedestrian as with social values. But, the normal motorist response in India is to increase the speed after sighting a pedestrian waiting at the kerb.

One would have expected Kerala, with almost every family having at least one relative abroad, to bring back foreign best practices. But my experience has been different. In one month in December 2021, I had about a half dozen near-miss events of motorists and two-wheelers grazing past me even when they had ample space on the road. On one occasion, when I was walking on the safer right side of a narrow road, a car whizzed past from behind, almost touching my elbow. He went so fast that an incoming scooterist stopped to enquire whether I was okay. Overall, they seem to bring back a taste for fancy and racy cars but not the values from foreign shores.

Apart from the above are issues of disabled access, filth and clutter, footpath design features such as inaccessible heights, narrow widths and varying levels, and overall safety and comfort. While there is a lot of research and work on walkability in different countries, including India, what we discuss here goes beyond mere walkability.

Approach to footpaths

Footpaths have existed for millennia, but for which migrations, conquests, and trade, even across villages, would not have been possible in pre-vehicle days. Some put them in western cities in the third century BCE (see here). Footpaths, as we know them today, were conceptualised only around the 18th century. Until then, pedestrians shared space with the ordinary carriage driven by horses, bullocks, or even human beings. But, the approach to footpaths has become more advanced in the past few decades, and there have also been calls and initiatives for moving cities away from vehicles.

The rest of this essay discusses urban footpaths. The countryside is a different story, with countries like the UK passing legislation to preserve some old footpaths.

…footpaths are immersive spaces and the experience of walking them is integral to the success of a street.

Jo Adetunji, Editor, The Conversation UK

Importance of sidewalks

I am using sidewalks, the preferred American term for footpaths, to mean not just a space for the pedestrian to walk safely but one which provides a wholesome experience which is what modern urban design literature keeps in mind. As we shall see, this goes beyond a mere walking experience.

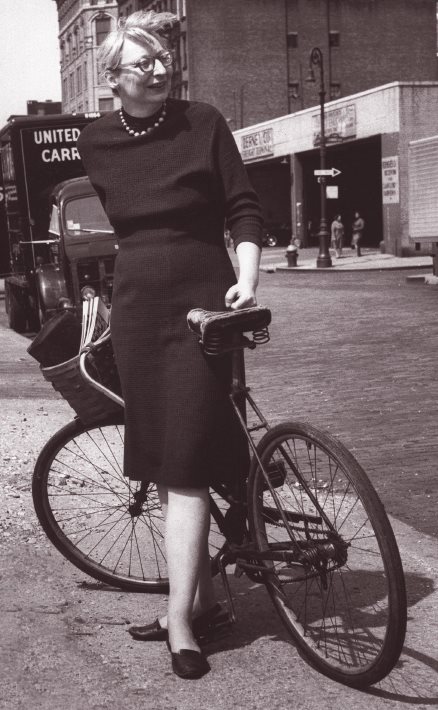

Jane Jacobs

Jane Jacobs (1916-2006), urbanist and activist (see here or here), and author of the hugely influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), identified four essential conditions for making great cities. One of them was pedestrian-friendly blocks.

Purpose of sidewalks

According to Jane Jacobs, sidewalks served three primary purposes: safety, contact, and assimilating children. Safety is obvious. She elaborates:

“…the public peace – the sidewalk and street peace – of cities is not kept primarily by the police, necessary as police are. It is kept primarily by an intricate, almost unconscious, network of voluntary controls and standards among the people themselves, and enforced by the people themselves.”

By contact, she meant that “…the trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts.” According to her, the concrete and tangible facilities required for these “happen to be the same facilities, in the same abundance and ubiquity, … required for cultivating sidewalk safety. If they are absent, public sidewalk contacts are absent too.”

The third purpose related to the role of streets in child rearing, where mothers allow children on them with the caveat to remain on the sidewalk. The rationale is to keep away from the streets where the cars are. But, if Jane Jacobs had seen how two-wheelers take over Indian sidewalks across all cities, especially during peak hours, she might have had to rewrite her book.

Jane Jacobs’ life was made into a movie (see here).

Sidewalks and children

The purpose of sidewalks for children was also incidental play:

“There is no point in planning for play on sidewalks unless the sidewalks are used for a wide variety of other purposes and by a wide variety of other people too. These uses need each other, for proper surveillance, for a public life of some variety, and for general interest. If sidewalks on a lively street are sufficiently wide, play flourishes mightily right along with other uses. If the sidewalks are skimped, rope jumping is the first play casualty. Roller skating, tricycle, and bicycle riding are the next casualties. The narrower the sidewalks, the more sedentary incidental play becomes. The more frequent too become sporadic forays by children into the vehicular roadways.”

Jane Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities, 1961.

In the prologue to the Spanish edition of Jacobs’s work, Manuel Delgado, the anthropologist, wrote that ‘the sidewalk determines the functions and the social, economic, recreational, cultural and vital purposes of a neighbourhood.’ Jane Jacobs called the wholesome experience the “ballet of the sidewalk,” complete with its spontaneity, co-presence, and diversity. Apart from “sidewalk ballet,” her writing contributed new and significant terms: “eyes on the street,” “human capital,” and “diversity of uses and people.”

Allan Jacobs

Allan Jacobs (a generation junior and, I believe, no relative of Jane Jacobs) of the University of California, Berkeley, describes what more sidewalks should include capturing that wholesome experience that makes urban life rich:

The sidewalks need every bit of space and, given what is on them, could use more. They are crowded with public and less public paraphernalia: kiosks, benches, bus shelters, clothes racks and book tables, tables and chairs at cafes, light poles, trees, many, many people, and, for long stretches, not-so portable metal crowd control fences, presumably there to keep people from spilling over into the street or crossing where that may not be the thing to do.

Allan B. Jacobs, Great Streets, pages 56-57.

Other views

Underlining the importance of sidewalks, Bedour Braker wrote in a symposium commemorating Jane Jacobs’s centenary as below.

“The streets, however, do not operate on their own. They need the sidewalks as their arms reaching out for pedestrians to enter and activate the function of the street as a public space. Together, they provide a setting for a healthy range of active and passive social behaviours.”

Jane Jacobs is Still Here – Proceedings of the Conference Jane Jacobs 100: Her Legacy and Relevance in the 21st Century, TU Delft, Netherlands, 2016.

King Charles III has long been deeply concerned about sustainable architecture and urban design. The eighth of his ten commandments on urban planning states, “The pedestrian must be at the centre of the design process. Streets must be reclaimed from the car.” That brings us to the next section on a case for less congestion in cities.

Case for less congestion

Inevitably tied to promoting the cause of the pedestrian is the call for fewer vehicles on the road. David Zetland, the environmental economist, who now teaches at Leiden University, makes a case for a pedestrian-oriented approach in his blog, The One-handed Economist. If you know President Truman’s famous anecdote on single-handed economists, Zetland’s blog title alludes to the need for firm views and action on critical issues. Because sometimes you want the answer. The footpath issue is one such. Zetland cites five benefits from lower congestion resulting from promoting pedestrians and bikers.

- Lower air pollution

- Less noise pollution

- Lower risk of injury from cars

- Fewer cars and parking means more space for pedestrians and cyclists

- Redesigned roads add mobility options without preventing driving

The bottom line, according to Zetland, is: ‘Redesigning streets away from cars raises the standard of living, accessibility, and environmental sustainability.’ I would add further, redesigning cities to prioritise walking, cycling, and public transport in that order.

Laurie Winkless wrote in Forbes that “a car-dominated transport sector also has health implications for those in and outside the vehicle. From the poor air quality that results from vehicle exhaust emissions and tire wear to driver, cyclist and pedestrian road deaths and noise pollution, having so many people reliant on their cars disadvantages everyone.”

A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation.

Gustavo Petro, Mayor of Bogota, capital of Colombia.

Various initiatives

Great sidewalks cater to different senses affected by the sights, smells, sounds, heat, shades, and textures. They offer a variety of speeds and activities depending on the location of the sidewalk. What is required are safe, continuous and engaging sidewalks that interconnect seamlessly and entice people into incorporating such walks into their daily routines. The trend is towards discouraging the use of private cars. Traffic calming measures have dramatically reduced critical events and casualties, even up to 60-80%, in many Western countries. At the same time, some other solutions, such as skywalks, have proved to be poor and impracticable. They are often deserted, unsafe, shabbily maintained, and misused by criminals. Moreover, as an alternative for the elderly and disadvantaged, they only add to miseries.

The European charter

The European charter for pedestrian rights, first enunciated in 1988, broadly covers the following:

- Right to live in a healthy environment and enjoy various amenities of life adequately safeguarding physical and psychological well-being.

- Right to live in urban or village centres tailored to the needs of the motor car and to have amenities within walking or cycling distance.

- Facilitate easy social contact and not aggravate weaknesses of children, the elderly and disabled

- Measures maximizing independent mobility of disabled

- Exclusive use of extensive areas harmonised with town organisation and with exclusive connections to short, logical and safe routes.

- Compliance with chemical and noise emission standards for motor vehicles, introduction in all public transport systems that are not a source of either air or noise pollution, creating ‘green lungs’, fixing speed limits, modifying the layout of roads and junctions to safeguard pedestrians and bicycle traffic effectively, ban advertising which encourages improper and dangerous use of the motor car, appropriate road signs, efficient signalling systems, motor vehicles designed with smoother projecting parts, make persons creating risk financially liable for consequences, and training drivers. In the last point, drivers are sensitised to sidewalker challenges and teaching them that right of way does not mean unfettered freedom.

- Right to complete and unimpeded mobility through integrated transport, including ecologically sound, extensive and well-equipped public transport, facilities for bicycles in urban areas, and parking lots that do not hinder pedestrian mobility or enjoyment of architecturally distinguished sites.

- Disseminate comprehensive information on pedestrian rights and alternative ecologically sound transport through appropriate channels, including schools, where children are also taught the basics of safe walking and cycling.

Walkable cities

This article lists the following as among the most walkable cities in the world: New York, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Paris, Venice, Madrid, Hamburg, San Francisco, Florence, Dubrovnik, Helsinki, Philadelphia, Boston, and Washington, DC. One may disagree with some, but it is nevertheless an eye-opener. And it is disappointing that none from India makes it there.

Let us see how three of these cities have incorporated extant ideas for sustainable urban spaces from a pedestrian’s point of view.

New York City

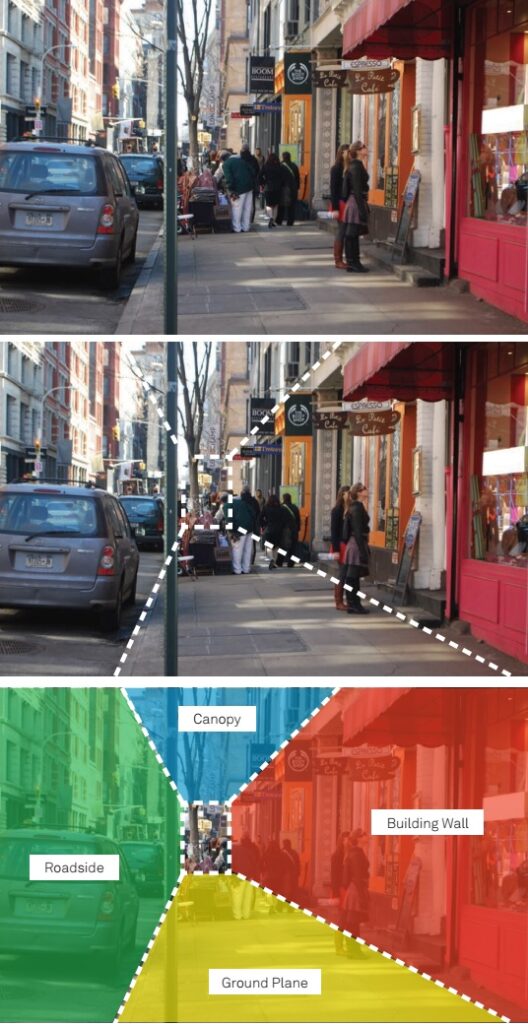

The New York City’s planning department provides design guidelines to help architects and designers. Footpaths are now conceptualised as a “room” with four surfaces: the flat pavement, the wall of the building facing the street, the roadside, and the canopy. The then New York City mayor, Michael Bloomberg, also a co-author, deemed it part of the initiative to fight obesity and lead a healthy life and initiated a study on sidewalks (download here for the major principles and guidelines, and here for the tools and resources).

The New York study imagines six factors that could contribute to a wholesome sidewalk experience: connectivity, accessibility, safety, human scale and complexity, continuous variety in speed and activities, and sustainability and climate resilience.

It attaches great importance to lighting:

“Lighting is crucial once night falls. Good lighting on people and faces and reasonable lighting for façades, niches and corners is needed along the most important pedestrian routes to strengthen the real and the experienced sense of security, and sufficient light is needed on pavements, surfaces and steps so that pedestrians can maneuver safely.”

The New York study indicates that such environmental interventions increase physical activity by 35–161%. Apart from street lighting, these interventions include “traffic calming approaches, enhanced street landscaping, improved safety and aesthetics in the physical environment, continuity and connectivity of sidewalks and streets, proximity of residential areas to destinations, and the use of policy instruments like better road design standards, zoning regulations, and government policies.” Studies also indicate that such interventions “are associated with an increased sense of community and a decreased sense of isolation, decreased crime and stress, and increased consumer choice for places to live.”

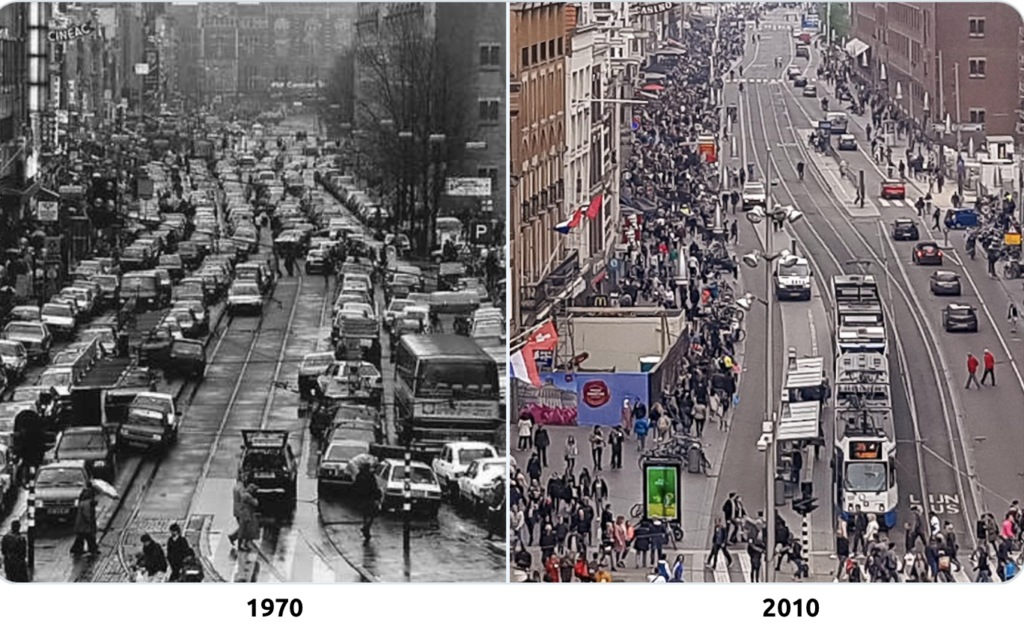

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is among the most important cities that have seen a significant makeover to give pedestrians their due. Among other things, The Netherlands has legalised jaywalking. Pedestrians are now allowed to cross anywhere, and there is no punishable jaywalking. See here and the images below:

Amsterdam, like Paris, seems to be the most talked about. But, other cities have also made drastic changes, namely, Tokyo and London, the latter even closing some roads to vehicular traffic depending on pedestrian use, not the size of the road. The significant change is in motorists losing what Oli Pritchard calls ‘unfettered primacy.’ For instance, car parks removed from residences and placed farther than the nearest bus stops have increased public commuting in London.

Paris

One of my memorable experiences walking anywhere was in Paris, spending a couple of hours at the McDonalds facing Le Jardin du Luxembourg, watching people pass by, and walking around the student hub on nearby Boulevard Saint-Michel before watching a documentary on Van Gogh (In a Bright light: Vang Gogh in Arles, 1984) for the second time in a small cinema at the Sorbonne University (watch the free documentary here). The cinema had full-length portraits of many directors, including Satyajit Ray.

Allan Jacobs describes the wholesome experience of Boulevard Saint-Michel thus, in his classic work, Great Streets:

“What makes the Boulevard Saint-Michel, in Paris, special is the light and the stores and cafes. The mixture of natural light that filters through the trees and the welcoming transparency of the ground-floor windows of commercial uses invites the passerby and calls attention to the goods displayed on racks or tables along the sidewalks. At the same time, even on a bright sunny morning, the shops and cafes are lit with incandescent and neon light that contrasts markedly with the deep shadows and shade cast by those same trees…

It is not so much the monumental apartment houses that line the boulevard, especially at the Place Saint-Michel, for there are long months when these can hardly be seen, blocked from views by the trees. Nor is it the Bernini-inspired wall fountain at its start, which rarely gets sun, nor the wonderful opening out at the Luxembourg Gardens, as impressive as that space is. Rather, it is the light and the shops.”

Allan Jacobs, Great Streets, 1993, page 9.

Paris Respire

Making human-scaled cities is not merely a technical challenge. The case of Anne Hidalgo, a socialist and environmentalist, shows that it is a political one. The first lady Mayor of Paris holding office since 2014, she won her second term handsomely in 2020 on the strength of her successful anti-car policy called Paris Respire (in English, Paris breathes). The scheme bans motorised vehicles on the first Sunday of every month while allowing certain exceptions (taxis, buses, and delivery vehicles) at a speed limit of 20 km. There is unlimited access for walking, biking, skateboarding and rollerblading. These days, bicycles and electric transport rides are free. The challenge addressed here is mainly environmental, but the pedestrian also benefits.

Hidalgo also increased parking fares while banning free parking on certain days. Also on the cards are 24-hour metro rides and a ban on diesel vehicles. At the same time, dedicated bike lines will soon be around 1000 km.

See here for the change in a Paris street. Matthew Parris, a journalist, identified support for tram and bike lanes as the central feature of the success. Planners and developers aim for a village ambience to make cities more liveable.

Paris will soon transform into a 15-minute city. In this scheme, “la Ville des proximités,” or “the city of neighbourhoods,” residents of every neighbourhood can access their essential needs within 15 minutes by walking or cycling. (See here)

The Indian case

Vehicle infrastructure

In February 2021, India set the first-of-its-kind world record; a single-lane stretch of 25.54 km (15.87 miles) was constructed in 18 hours. Around the same time, NHAI and Patel Infrastructure created another world record for laying concrete on a four-lane highway in 24 hours. The feat made it to the India Book of Records and Golden Book of World Records. In another record in March/April, contractors constructed a 2.5 km (1.5-mi) 4-lane concrete road within 24 hours. (see here).

These are commendable. But, the pedestrian has long been missing from these transport policies. Pedestrians and cyclists continue to have a more than proportionate share of fatalities. When roads for motorcars and other vehicles developed, footpaths were made in return for the roads rightfully belonging to pedestrians for millennia. Only a fraction of the cost of building road infrastructure would be required to ensure the first stage of an excellent sidewalk experience: building safe and convenient footpaths.

Whither the pedestrian

With India heading the G20, where most member countries have excellent walkable cities, visions for a new India should prioritise its pedestrians’ interests. Ultimately, it will not be the GDP contributed by motor vehicles sold and money spent on infrastructure that counts but the happiness generated by a healthy life.

Pedestrians are now treated as unavoidable obstacles in the way of vehicles. On the other hand, from “the history of pedestrian safety in Western Europe, it can be seen that the image of the pedestrian has gradually been changing from “a moving obstacle in the way of vehicles” to a means of transport of its own right, with its own constraints and travel objectives.” (Muhlrad, 2007)

Transport policy should, therefore, be about moving people and not moving vehicles, as stated in the National Urban Transport Policy of 2006. But, the government continues to prioritise vehicles over pedestrians. Thus, there has hardly been any change on the ground, literally.

The focus is on providing space for a few feet to walk on. Forget about fantastic ideas of the four dimensions of a sidewalker’s space that modern urban thinkers conceive of, namely, the ground, the roadside, the building side, and the canopy above, each varying according to the nature of the area: business, downtown commercial, main neighbourhood street, or residential.

Road makeovers to facilitate vehicular traffic through flyovers, including clover-shaped ones, have not only ignored pedestrians but inconvenienced them. The CSE report notes how the New Delhi AIIMS flyover made pedestrians walk several hundred more metres through narrow and unsafe paths to reach the nearest bus stop or Delhi Haat diagonally opposite.

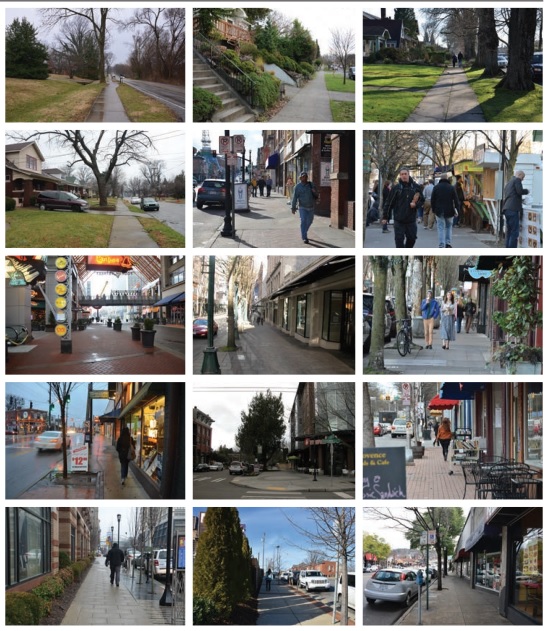

Walkability ranking

Pedestrian-friendly blocks, as Jane Jacobs envisioned, would be a faraway dream. What a pedestrian in India can hope for now are a few streets where they can walk safely. For this, it is helpful to look at how streets in India fare. The indices used for this typically employ the following factors: conflict with other transport modes, availability of footpaths, amenities therein, disabled access, obstructions, safety from crime, availability of crossings and connections, and motorist attitudes. One has to therefore take things stage by stage.

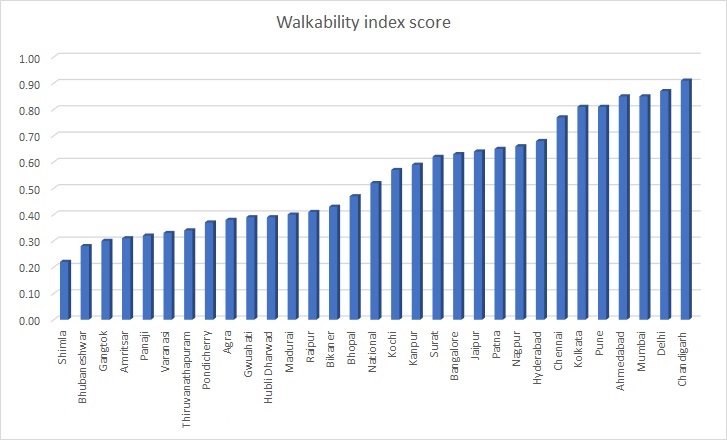

The position of different Indian cities in a study by Wilbur Smith Associates for the Ministry of Urban Development placed different cities as below:

Wilbur Smith Associates for the Ministry of Urban Development

Understanding the graph

Not surprisingly, the planned cities of Chandigarh and New Delhi occupy the top ranks. But, the best itself is not good enough, going by the CSE walkability report, which primarily focuses on Delhi. That probably explains why Mumbai and Pune are among the top five despite a poor walkability record, barring an odd Marine Drive or a Worli Seaface. It only perhaps means how bad the other cities I am unfamiliar with might be. Also surprising is Bhubaneswar, another planned city designed by Otto Königsberger, the German architect and Indian citizen, second from the bottom. At the same time, I am not surprised that Trivandrum is in the bottom quarter. Varanasi might have moved up, but why are Shimla, Gangtok, and Panaji in the bottom five?

Chennai’s top quarter position is also not justified by news reports, anecdotal evidence, and my experience. It, along with Hyderabad, does not deserve to be above the Jaipur I know. Pedestrian plazas have been introduced in Chennai with much fanfare and World Bank funding. But, from early morning, starting with news vendors, two- and three-wheelers and even four-wheeled garbage vans pass through the wider gap in the bollards intended for the tricycles of physically challenged and pram-pushing mothers. Two-wheelers regularly drive on the wrong side, and vehicles cutting across the pedestrian pathway do not recognise the pedestrian’s right of way. Shops, itinerant vendors, and signages deny the pedestrian a free and unobstructed walking experience.

My recent experience

After about a decade, I started driving again. Though a licence holder from the late 1970s, I don’t particularly enjoy driving. But with the roads unsafe to walk, there is no choice. As written above, within six weeks of landing in Trivandrum, there were as many incidents of motorists almost fatally grazing past me even when I was on the right, and the driver had ample space.

In my experience, the most walkable city in India is New Delhi. But that too only select stretches mostly confined to the Lutyens-Baker part of New Delhi that provided for expansive footpaths laid almost a century back. They were as comfortable for walking in the early 1980s as they were three decades later when I sometimes cycled to friends’ houses for dinner. But, even New Delhi does not have dedicated bicycle lanes. Moreover, in the upmarket residential localities, residents have, since the 1980s, taken over footpaths for parking their additional cars.

Way forward

The Indian pedestrian is angry. The resentment is deep. But, they are helpless and are no doubt the silent majority. There is public acceptance of the need for change. Elderly people in Chennai stood vigil on footpaths to keep two-wheelers off them. When pedestrian societies organised protests in many parts of the country, motorists welcomed them. This showed that many opt for independent vehicles only because the roads are not pedestrian-friendly, and public transport is poor.

Some of the following could be incorporated in a separate pedestrian manifesto. Such a manifesto would be about the silent majority, mostly the elderly, disabled, poor and disadvantaged. Imagine the elderly lady crossing over to buy groceries, perhaps even unable to walk up to the nearest zebra crossing. (see image alongside)

Approach and design

The pedestrian is not to be viewed as an obstacle but as another moving vehicle with a higher claim and priority and access to public roads subject to certain restrictions. The policy planner should, therefore, not look at the required changes and regulations from the inside of a car but from the point of view of a pedestrian. Urban design should accordingly respect and factor in the pedestrian’s tendency to choose the shortest walking distance. This will help overcome common ills such as jaywalking and median climbing.

Following the above principle, one should avoid unacceptable schemes such as skywalks. These are easy and escapist shortcuts to avoid the more difficult task of controlling vehicles and giving back the roads and footpaths to pedestrians. Apart from being eyesores on the cityscape, skywalks and subways without lifts or with non-working lifts is a cruel joke on the sick, elderly and the physically challenged, who form a significant group among pedestrians.

Based on experience worldwide, best walkability principles should undoubtedly form part of the essential criteria for smart-city projects and other similar schemes.

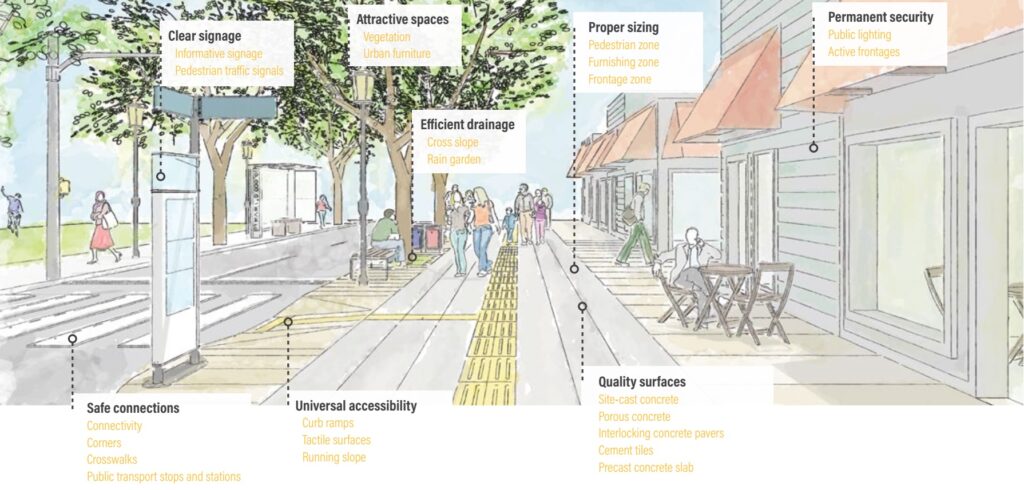

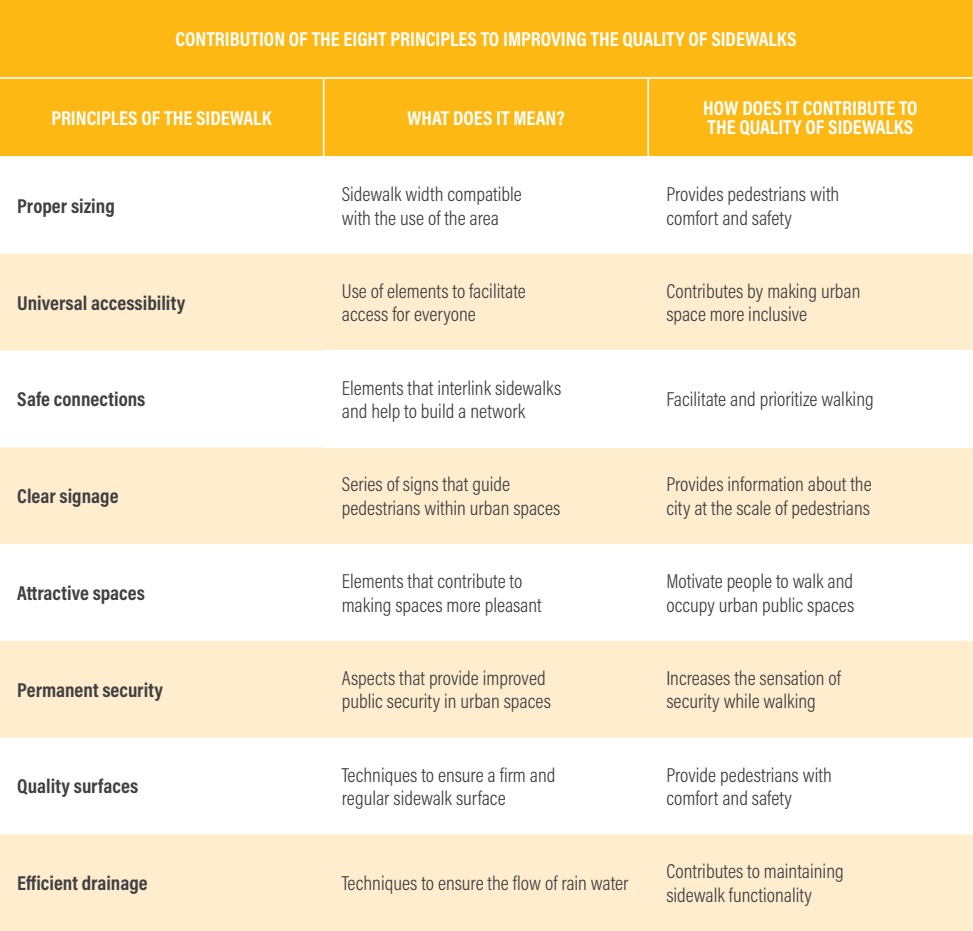

Here, the eight principles of sidewalks (World Resource Institute, Brazil, 2019) are also relevant, as described in the image below:

The benefits of the eight principles are explained in the chart below:

Walking is the most democratic way to commute. It is the oldest and most common mode of transport in the world, not to mention being a far healthier option – for both people and cities.

World Resource Institute, Brazil. The 8 Principles of Sidewalks – Building more active cities, 2019.

Rules

Based on the above broad principles, laws and related rules/regulations should prevent footpath space reduction. The administrators and the driving public should also be sensitised to the rights of pedestrians. This will avoid situations like when the Law Commission considered imposing penalties, including imprisonment, for pedestrians. They did not appreciate the constraints under which the pedestrian is forced to walk on the carriageway.

Vehicle owners could also be required to walk to their parking lot, as required in some countries. This will sensitize them to a pedestrian’s view and challenges. This was done by banning parking inside or outside apartment blocks. They had to shift their parking farther than the nearest bus stop or metro station to incentivise the use of public transport. Similarly, the ‘bungalowed’ should not be allowed to park on footpaths outside for want of space within their compounds.

What businesses, like cafes and florists, could be allowed to spill onto sidewalks, and to what extent, and when and where they need to be regulated should be laid down.

These regulations must be framed with broad consultation, including with local bodies and representatives, to enhance legitimacy.

Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.

Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Education

Drivers’ attitudes and behaviour, speeding and other noncompliance with traffic rules, often due to fatigue and under the influence of alcohol, cause accidents where pedestrians and cyclists are the most significant casualties. Therefore, educating vehicle drivers is essential to enhancing the pedestrian experience. Whenever I have had to step onto a road, the look on the passing motorist’s face conveys the message, how dare you encroach on my area. The motorist should be conscious that her rights to the road are only secondary to that of the pedestrian.

I have seen in one city where the testing official watches as the driving school instructor and licence applicant pass by in their cars. While the applicant has his hands on the steering, the instructor controls the specially designed vehicle. This might be an extreme example. But, by widespread consensus, licencing in India has been a joke, characterised by high bureaucracy and low testing of anything.

On the other hand, I have heard of applicants in many European countries and even in the Gulf countries having to undergo several rigorous tests and failures before being issued a licence.

Enforcement

One of the reasons why such corruption takes place in licensing is because they are viewed as victimless crimes. This is an area perhaps some behavioural thinking has a place. Whenever a driver is involved in a severe accident, the information should be conveyed to the official who cleared his licence. An official should, of course, be designated to take ownership of each licence.

Another reason is that RTOs have been overwhelmed by the number of applicants. Along the lines of the issue of passports, there is a case for streamlining the processes. Driving schools could be licensed, regulated, and acted against when their learners are involved in accidents beyond a threshold. Licensing itself could be outsourced, as in PUC testing.

The public, including residents, could be involved as volunteers and empowered in enforcement when encroachments and two-wheelers take over footpaths during peak times. They could, among other things, be authorised to restrain such vehicles until the police arrive.

The police should also not ignore minor traffic violations. Those who violate one set of standard regulations are also most likely to violate other laws. Therefore, the database will be helpful at some stage, as they could be involved in related crimes in the neighbourhood or elsewhere.

The impact of penalties is a product of the probability of detection, the likelihood of penalty, and the severity of the penalty. To retain the burden or deterrent uniform, the penalty should be higher at times, such as late at night or early morning, when policing and the probability of detection are low.

Safety measures

According to Jane Jacobs, getting more people on the streets, especially the sidewalks, enhances safety as they, especially the florists, other vendors and regular walkers, become effectively ‘eyes on the street.’ At the same time, one should also ensure sufficient CCTV coverage to provide added safety during odd hours.

Best practices list many safety features. This includes staggered crossing and well-designed pedestrian islands. Excellent and well-designed connections also ensure that pedestrians don’t have to jump dividers to get to the other side. Safety measures also include the use of standardised signage and road markings.

Other amenities

Pedestrian light-controlled (pelican) signals or pushbuttons to help the pedestrian request for crossing, including its variations (puffin, toucan, etc.), must be positioned where appropriate.

Traffic calming

The authorities can think of various traffic calming measures. This includes work from home, which became popular during the pandemic and has remained long after. Can we tax incentivise those working from home, as they commute less? We could also incentivise those using public transport. Even employers allowing their employees to work from home could be incentivised.

At the same time, one must be strict with traffic penalties and parking fees. Toll charges should be graded according to the number of passengers and not per car, the charges being higher for a single user or underused cars.

The other traffic calming measures include speed breakers appropriately positioned, raised crossings to slow down cars, and limiting car speed to walking speed in certain areas, as in what the Swiss call Begegnungszonen, or strolling zones.

Park-and-ride facilities in the suburbs and near public transport will incentivise the public to use public transport and reduce traffic in city centres.

Finally, as in Paris, Amsterdam, and other cities, declare entire areas, if not cities, car-free. Such pedestrianisation could be considered in big city centres, as in large market areas, such as Parrys Corner and Panagal Park areas of Madras, Fort in Mumbai, Connaught Place, Khan Market, Sarojini Nagar, and other major market areas in New Delhi, and Chalai area in Trivandrum. Retailers should support this initiative as global experience has reported a considerable increase in sales and property value post-pedestrianisation.

Lead by example

It is rare for an Indian policymaker, including politicians and bureaucrats, to walk on public roads after they cross the threshold beyond which such walking becomes infra dig. By walking, I mean unaccompanied by hangers-on, security, and other paraphernalia. This probably explains why many traffic initiatives have been pedestrian-unfriendly.

Introducing change in India is difficult. In the issue of pedestrians, there will be the usual naysayers who will list many excuses citing crowd, climate, population, etc., to argue why global standards are not practicable in India. Once the Central Vista project is ready and the residences of many ministers come within the vicinity of the new Parliament and government offices, I hope they will walk the talk by walking their way to the office. Setting the tone from the top is the best way of ensuring compliance by the rest of the country.

Public pressure

RK Laxman, the voiceless common man’s cartoonist, surprisingly drew more cartoons on traffic congestion, and the plight of car drivers and traffic cops, than that of the pedestrian. But, there was one cartoon of a crossing in South Mumbai, near the Flora Fountain (Hutatma Chowk), where the police reduced the pedestrian road crossing time from three minutes to one. There was a hue and cry from members of the public who use the connection daily to reach either Churchgate or VT Station. Laxman drew a cartoon of people waiting on their toes to dash across when their light becomes green. The message was conveyed, and the cops restored the original wait period.

While public pressure can be brought through cartoons, Indian cities can also be rated according to their walkability and pedestrian-friendly features, as in the case of cleanliness rankings. Pressure can thus be put on authorities in underperforming cities to get their act together.

Hope ahead

Hope comes from a corner in the North East, apparently India’s only silent city, Aizawl, Mizoram. If this is true, the message needs to be spread. See here.

The most important public places must be for pedestrians, for no public life can take place between people in automobiles. Most public space has been taken over by the automobile, for travel or parking. We must fight to restore more for the pedestrian.

Allan Jacobs and Donald Appleyard, Towards an Urban Design Manifesto, 1987.

(https://www.itdp.org/where-we-work/south-asia/india/)

Conclusion

Every human being is a pedestrian at various stages in life. Even a vehicle owner has to walk near public utilities, one’s office, children’s schools, hospitals and railway stations. Walking is the last leg of transport from the nearest metro or bus stop in any multimodal commute. The pedestrian needs to go to the top of priorities, where she belongs. Let us reclaim our footpaths from the metallic monsters and the mindless ones who drive them.

India remains where western countries were in the 60s and 70s and prize vehicle ownership. Changes favouring the pedestrian have been halting and half-baked. Islands of underperforming pedestrian plazas might win funds, press, and eyeballs. The government should support a nationwide movement to create a wholesome pedestrian experience in different stages.

These stages should prioritise safety, convenience, and accessibility. Thereafter conveniences such as street furniture, appropriate trees, waiting islands, dedicated cycling lanes, and traffic calming measures could be introduced in a time-bound manner. One is not going into details such as gates, fountains, benches, kiosks, paving, lights, signs, and canopies, all of which contribute to the sidewalk experience that makes streets great (Allan Jacobs, Great Streets, 1993). The initial focus should be on a minimal experience of safe and unhindered walking as a pedestrian’s fundamental right, just as it was during the times of a Shankaracharya, Huien Tsang or Ibn Batuta, who crisscrossed the country walking.

The priority should be to make pedestrian walkways safe, add quality and amenities to them one by one, and make them lively. In other words, first, save the skin. Thereafter, provide facilities catering to different senses of smell, ears, eyes, and the heart. It is a long way to making the common man the “natural proprietor of the street”, as envisioned by Jane Jacobs.

Postscript

This post started out being brief. It was never intended to be exhaustive. There are many pedestrian challenges left uncovered. Nevertheless, I hope it will encourage my readers to read more, spread the message, and generate some thinking, discussion, and policy initiatives.

Select References

In addition to those already referenced or linked above, I suggest the following:

Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, Better Streets, Better Cities, 2011. https://www.itdp.org/2011/12/22/better-streets-better-cities/

Janan Ganesh, Why I, a non-driver, wish the car well. Financial Times, London, 8 October 2022.

Nicole Muhlrad, A short history of pedestrian safety policies in Western Europe, 2007.

Roberto Rocco, ed. Jane Jacobs is still here. Proceedings of the Conference Jane Jacobs 100: her legacy and relevance in the 21st century. TU Delft, The Netherlands, 2016.

Jane Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities. Vintage Books, 1961.

Jane Jacobs, The economy of cities. Vintage Books, 1970.

Allan Jacobs, Great Cities. MIT Press, 1993.

Centre for Science and Environment, Footfalls: Obstacle course to livable cities, 2009.

Wilbur Smith Associates and Ministry of Urban Development. Study on Traffic and Transportation Policies and Strategies in Urban India in India – Final Report, 2008.

Advait Jani and Christopher Kost. A guide to creating footpaths that are safe, comfortable, and easy to use, Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, 2013.

Santos et al. The 8 principles of sidewalks – Building more active cities. WRI Brasil, 2019.

Bloomberg et al. Active Design: Shaping the Sidewalk Experience, New York City, 2013.

Bloomberg et al. Active Design: Tools and Resources, New York City, 2013.

US Government page: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike/ped_cmnity/ped_walkguide/sec1.cfm

Future reading

I was introduced to the following books towards the end of my first draft and never completed them. The two by Speck are brilliant. As he claims, if you read his Rules book once, you will know more than what 90 per cent of the people working in the area know. Read it twice, and you are eligible for the planning commission. Read it thrice, and you can start your urban design consultancy. I plan to read it only once.

Jeff Speck. Walkable City Rules – 101 steps to making better places. Island Press, 2018.

Jeff Speck. Walkable City – How Downtown can save America, one step at a time. Northpoint Press, 2013.

Jennie Middleton. The Walkable City: Dimensions of walking and overlapping walks of life, 2021.

(c) G Sreekumar. I last edited this post on 18 January 2023.

![]()

Welcome back! Interesting post on why the pedestrian is cross!!! Congratulations on the research inputs that have made the article eminently readable. I hope the authorities in India will wake up to the ground realities and take corrective actions to ensure that the sidewalks are given their due…

Thank you.

Many many thanks , for this well being esearched, well written piece .

Hari Ratan messaged this comment requesting me to post here as he is unable to do so:

“This is a fantastic piece of writing and needs to be published. I hope social organisations such as Rotary and Lions take up this issue and, with their reach, up to the highest levels of urban administration. Thanks for this.”

Thank you, Hari, for your kind words.