The practice of tipping and its motivations, and how it might be promoting a culture of bribery and corruption

Around 1990, a colleague shared a real story of a bank branch manager in remote rural Punjab. A borrower wanted to give the manager a gift. It was expensive. New to the job, he resisted. But, the borrower rationalised that he was only sharing in the happiness of having become rich thanks to the loans the bank sanctioned his firm. The incident points to the progressively fine divide between gifts, donations, kickbacks, bribes, extortion, and so on. Tipping is a related, though socially accepted and frowned upon, practice of sharing a monetary equivalent of perceived excess of value over and above what you paid for.

The story set me thinking whether politicians similarly rationalise bribes as a legitimate share in the ‘happiness’ of their subjects. This is of course too simplistic, as bribes serve different purposes, to do legal and illegal things, to look elsewhere, close the eyes, speed up files, and so on. Nevertheless, I wanted to compare tipping suggestions from Lonely Planet guides with the corruption rankings of Transparency International (TI). Other preoccupations delayed it for far too long. About a decade back I discovered that some others had done a similar study. Torfason et al. (2012) correlated TI’s Corruption Perception Index with tipping practices. For the latter, they used The International Guide on Tipping, instead of Lonely Planet guides. We will discuss their findings at the end.

History of tipping

There are different theories on the origin of tipping. Some date it back to the Roman era or even earlier. One puts it in the Middle Ages when lords travelling long distances would toss coins at beggars on the roads in unfamiliar territory. This apparent altruism was probably in exchange for safety. During the same period, the lords of the manor would pay their servants extra to appreciate some work. Another theory puts their origin in Tudor England where visiting guests compensated servants for the extra work on account of their visit. The practice that originated in Europe spread to the US through immigrants.

One version explains TIP as an abbreviation for “To Insure Promptitude”, but this looks more like a post facto justification. Yet another thinks that “tip” may come from a stipend, which originated in the Latin “stips”. At least in the context of restaurants, the version I had heard and believed in was that a tip was something the customer placed on the table up front as a promise of payment for good service. Whatever it was, the practice had its origins in Europe. Immigrants apparently exported it to the United States which was where the practice got institutionalised. Britain would have also exported to other countries through their colonies which explains tipping in Canada. But it does not explain the relative lack of tipping as an accepted practice in Australia or New Zealand.

Michael Lynn of Cornell University wrote that “the greater a nation’s level of neuroticism the larger the number of service professions that it is customary to tip in that country. This finding provides some support for an anthropological theory that tipping evolved as an institutionalized means of reducing service workers’ envy of their customers.”

Attempts to abolish

Movements to abolish tipping started as early as in late 19th century. “Gunton (1896) called tipping offensively un-American because it was contrary to the spirit of American life of working for wages rather than fawning for favors.” It was seen as creating a class looked down upon by the tippers. Many states in the US banned the practice, starting with Washington in 1909, only to be repealed many years later.

Growth of tipping

In Europe, the practice has been to round off the restaurant bill. Adding around 15-20 per cent seems to be a typical American practice. In the US, this percentage grew over the years. It was 10 per cent from the nineteenth century for many decades eventually rising to 15 per cent. Writing in her etiquette manual in 1997, Post considered 15 per cent of the bill, excluding tax, as generous even in elegant restaurants, but the figure was moving towards 20 per cent. Some travel guides now put the standard tipping at 15-25 per cent. Competitive tipping among customers, aided by one-upmanship and vying for attention, explains why tipping in the US doubled over a century.

Not only has tipping in restaurants grown, but it has also spread to other sectors. Starting most ubiquitously with restaurant servers, to use a more gender neutral term than waiter/waitress. It spread to taxi drivers, and now covers food delivery, bartenders, and hair salon workers. Today, even gig workers, supposed to be their own bosses, expect tips. The International Tipping Guide, which Torfason et al. used in their study, lists more than 30 such services. In this post, I will draw examples mostly from restaurants, which most people are familiar with as compared to caddies in golf courses.

Do travel guides surreptitiously promote tipping? After all, they seem to be funded by the hospitality industry, through advertising or otherwise. How tipping spread across which countries and sectors could be the subject of a future study using a neo-institutionalist approach.

Tipping is a voluntary payment that a consumer can do without. Nevertheless, it is big-time money. Tipping in the US alone accounts for about USD 40 billion a year, enough to fund two NASAs (Azar, 2020). That brings us to what explains tipping.

Explaining tipping

Economic rationale

Economics has an explanation for tipping also. Please listen to the three nearly one-hour long Freakonomics podcasts with links at the end. One explanation is based on the principal-agent relationship between the restaurant manager/ owner and the server. The manager does not have the time or resources to ensure that every customer is served well. Tipping transfers this responsibility to the end-user who is expected to vary the tipping according to the quality of service.

This to me is a post-facto rationalisation for a practice that has evolved. It does not also explain tipping in other sectors. It also does not also hold good when it comes to solo service providers such as hairstylists, caddies, and cab drivers in a gig economy.

When other social and cultural factors come into play, as discussed below, the economic rationale seems irrelevant. For instance, if the customer pays a standard tip irrespective of the quality of service, whether due to social norms, compassion or otherwise, there is no longer an incentive to go the extra mile to provide better service.

Another economic rationale could be a customer’s perception that his server is not paid well. Or when the services are underpriced, as in a government department, the intermediary, say a peon, expects a share in the rent for locating that elusive misplaced file. Nevertheless, the question remains why a rational consumer one encounters in an undergraduate Economics textbook would pay more than the price contracted while ordering from the menu? For that, we need other factors.

Cultural factors

Tipping could be the result of psychological, social and cultural motivations which seem more plausible than purely economic reasons. Culturally, it could be a practice imported from elsewhere or evolved over a long period.

Social influences

Socially, it could be to avoid the tag of ‘stiffing’ or cheating someone out of their due. It could also be due to not wanting to be the odd person in a group. Some see tipping as proper etiquette. Others do it to ensure better service next time. But such motivations for tipping are irrelevant for customers like tourists who have no intentions to return to the same place or service provider. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that a cab driver will be repeated. Even if it happens, it is unlikely that he will recognize the passenger or the tip paid earlier. Moreover, her ability to adjust the quality of service to the anticipated level of tipping is also minimal.

The motivations of all those concerned – the tippers, servers, and restaurant owners/managers – could combine into a self-reinforcing and self-sustaining social norm to show gratitude and supposedly increases welfare. In the absence of such a social norm, as for inflight service, people do not feel guilty for not tipping.

Tipping becomes self-reinforcing, self-sustaining and self-advancing when people tip more than socially accepted levels. This happens when they want to have a feel-good factor of being generous, impress their guests, express gratitude, or for other reasons. In one study, more than 2/3rd respondents indicated showing gratitude as a reason for tipping.

Psychological motivations

Some look at their tipping as an expression of gratitude for an intangible that approximates an ‘at home’ feeling, or for experience exceeding expectations. Applying reverse logic, not tipping is equivalent to expressing unhappiness which may not be polite. The origins of tipping also show it as a show of gratitude for greater perceived value than what was paid for. But, by its nature, it had become contagious. For the more practical-minded, tipping could even be just due to not having change or not wanting to carry change. Hence the expression, ‘keep the change’.

Among other psychological factors is the ‘warm glow’, or wanting to be a person who does that kind of thing. Relatedly, one also feels like paying more for a job that one wouldn’t like to do oneself.

Related to a psychological motivation is one-upmanship, to show off to family and friends. A particularly affluent Indian once took me to Rasika, the top Indian restaurant in Washington, D.C. The way the servers interacted with him, it was clear that he was a regular customer. After the meal, when he left behind a twenty-dollar bill (or was it per cent?), the lead server, a white man, whispered into his ear that even the locals do not leave more than ten dollars. The year was 2013. My friend was proud and happy. So was the server who, with his comment, ensured that the tipping level will be continued on the next visit.

Service quality

As tipping follows the service delivery, only the tipping can vary. Service cannot adjust to the level of tipping unless if anticipated based on other factors. In surveys, customers responded that their tipping was highly sensitive to service quality. But, in reality, research showed that tips are only moderately sensitive to service quality. The low sensitivity of tips to service quality is a ‘tipping-service puzzle’ where servers could be better off saving their efforts on service quality which hardly affects their tips (Lynn and McCall). In my view, the low correlation is because the relationship is not linear. There is an upper limit and a kink below which if the service quality falls, tips fall dramatically.

Variations in tipping practices

In reality, irrespective of the nature of service, tipping practices varied for altogether different reasons. In the same hospitality industry, one tips bellboys, but not the receptionist. One may tip the valet who brings your car but not the security guy who navigates the reversing of your car. Among those who also provide personalised attention but are not tipped include flight attendants and nursing staff. But these practices are changing slowly and you might never know which area soon comes under the hold of ‘tipping’. For a takeaway from a restaurant, a service no different from a grocery store or a chemist, there are expectations of tipping. Some may even ask you to sit, to recreate a ‘being served’ experience.

Research evidence

What does the research show? John List, behavioural economist at the University of Chicago, and a potential Nobel Laureate, ran a gigantic economic experiment with 40 million observations when he was Chief Economist at Uber. Cumulative tipping in Uber was about 4% of rider charges as against 15 to 20% in restaurants. Interestingly, the driver’s income does not increase on average due to tipping. When the app has a tipping option, more drivers come in and bring down the wages. Combined with tips, it leaves the earnings more or less at the same level.

Demand-side variables explain roughly three times more of the observed tipping variation than the supply side or features of the trip explain. These are elaborated below:

Uber rider factors

- Nearly 60% of them never tip, 1% always tip, and only about 40% sometimes tip, but not always, based on some aspect of their experience.

- Demand-side factors such as rider gender, rider rating, and their previous

experience with Uber are each important in explaining variations in tipping. - One out of six drivers were tipped post facto.

- Rider ratings are positively associated with tipping. Five-star rated riders had more than double the chance of tipping than those rated 4.75.

- Gender matters in tipping. Men tip 12%-17% more than women. This goes against evidence elsewhere of women paying more for charity. Is visibility of the outgo a factor?

- Gender also interacts with age, with men tipping younger women more than they tip any other group.

- Given an option, most do not tip, irrespective of service quality.

- Riders tip less as they take more Uber trips.

Uber driver factors

- Supply-side factors such as driver gender, age, rating, and experience as well as

trip features explain variations in tipping. - Driver ratings are positively associated with tipping. Five-star rated drivers had double the chance of being tipped than those with 4.75 rating.

- How a driver drives. Quality of ride matters as well, with higher quality generating higher tips.

- Age of car, with older cars getting less tips.

- The language the driver speaks. Those who change their default language from English get less.

- Female drivers are tipped 10%-12% more than male drivers. They get more from both male and female passengers.

- Younger female drivers receive more tips than comparably-aged male

drivers. As older female drivers get less tips, this disparity shrinks over time, and disappears completely by age 65. - Drivers receive less in tips as number of trips increases, due to a lower

likelihood of receiving a tip on any given trip.

Heterogeneity

- There was significant heterogeneity in race, income, and education across the quintiles for both drivers and riders

- Heterogeneity in people’s behaviour. Variation in tipping outcomes across riders is three times more important than variation across drivers.

- Substantial temporal and spatial heterogeneity in tipping. Tipping is highest during very early morning hours, between 3:00 am and 5:00 am. These are mostly airport and business trips where riders get reimbursement. A disproportionate percentage of airport and business trips takes place during these hours. This reflects income effect or generosity with other people’s money.

- Tips are also high on Friday and Saturday evenings around 6:00 pm. Tips are lowest around midnight.

Other factors

Pre-set tipping options on taxi apps influence tipping decisions and the extent of tipping. Higher levels mean tipping less often but a higher total amount.

What the data showed is the heterogeneity of behavioural patterns. People liked to be seen as generous. But, List concluded that very few people will be continuously and consistently generous.

The level of tip and the fare are positively associated in a concave manner. On average, a 10% increase in fare is associated with a 2.5% increase in tip.

Repeat rider/driver interactions increase tip levels, but the mechanism is not due to strategic reciprocity or conversation-based social interaction explanations. Greater exposure itself seems to induce higher tips.

What I would like to know more from future research is whether tipping is more when one is in a group as compared to travelling alone. Also, does tipping increase the chances of getting your next ride and a better-rated driver? In other words, is there true reciprocity or a shade of extortion?

Demographic differences

Certain demographic differences in tipping behaviour have already been mentioned. Certain others are as follows:

- Tipping varies based on where the rider and driver are from.

- Tipping differs by ethnicity of tipper and tipped worker. Blacks tip less than white, in number and average amount. This is also influenced by socioeconomic status for blacks.

- The above is explained by differences in perceived injunctive and descriptive tipping norms. Injunctive norm is what one feels one ought to do. Descriptive norm is about what people actually do. Only 1/3 blacks approve of tipping 15 to 20% as against 2/3 of whites. On the other hand, most blacks think people don’t actually pay that much.

- Both Black and White passengers tipped white drivers 1.49 times more than black drivers. This suggests that higher tips to white drivers are not due to prejudice but a perceived higher service quality.

- However, for perfect service quality, white servers earned much higher tips averaging 23.4 percent, whereas black servers still received 16.6 percent

- Older people tip less. And they look more at service quality.

The lower tipping by minority groups probably indicate their sensitivity to service quality could be higher than that of other groups. This should incentivise better service to them.

Given the robust ethnic differences in tipping behaviour, a natural question is whether servers discriminate against those who are expected to be poor tippers.

Lynn concluded that customers give more tip to occupations with these characteristics: “workers are less happy than customers during the service encounter; the workers’ income, skill, and required judgment are low; the workers deliver customized service; and customers can more easily evaluate workers’ performance than managers can. The last item implies that tipping is more common where it yields higher economic efficiency.”

Tip enhancing server behaviour

The spread of tipping has also led to innovative practices among servers and other service providers aimed at nudging the service user into paying higher tips. Thus, if you see any of the following behaviour that is probably because past experience correlated them with higher tips:

- Customers tipped significantly more when they were touched by the server, on the shoulder or elsewhere, than when they were not touched

- Squatting next to the table or sitting down at the table on a server’s first visit increases tips.

- An innocent piece of candy that arrives with your bill. The size of the candy could also determine the size of the tip.

- drawing a smiley on the bill

- forecasting good weather

- telling a joke

- wearing a flower in the customer’s hair

Perhaps other gestures would include bringing a toy for a child, special attention to the elderly, or child-friendly table and chair to the amusement of all.

Other issues with tipping

Equity in restaurants

Tipping increases the pay to front end staff, who typically require only short periods of training, as compared to the kitchen staff who require years of education and apprenticeship. This gives rise to equity issues and pressures to go for the pooling of tips or replacing tipping with automatic service charges or service-inclusive pricing.

Discrimination

The demographic divide between who receives how much and how often based on race, sex, age, etc., as we discussed above, points to the discriminatory effects of tipping. It deepens the racial divide and perceptions of the ‘other’. Unfairness arises when certain categories receive less tips for reasons other than mere service quality.

Tipping enforces archaic and undesirable social distinctions and facilitates discrimination in who holds what jobs in a restaurant. It could also encourage sexual harassment.

Discrimination comes when the visible bellboy gets tips while the invisible housekeeper who probably does more hard work over a longer period gets paid far less by way of tips, if at all.

What influences these tipping preferences? Apart from visibility, attractiveness also plays a role. Attractive female servers get more tips. Slender women get more than fatter women while those who are better physically endowed get more than those who are not. Blondes get more than brunettes. Women in their 30s get more than teenagers.

Thus getting ones employees to rely on tips as part of their compensation has an inbuilt discrimination.

Eliminating tipping

Daniel Meyer is a successful restaurateur who owns ten top-class restaurants in the cutthroat New York market. The success of two of his restaurants, including the Indian restaurant, Tabla, now closed, was the subject of an acclaimed documentary, The Restaurateur (2010). In 2015, Meyer decided to eliminate tipping. He had earlier banned smoking in his restaurants ten years before it became the law in New York.

Meyer reported that before introducing the service charge, his servers were making, on average, over twice the wage of the cooks. The results of the change were as follows:

- The gap narrowed between formerly tipped front-end and untipped kitchen employees

- But, customers were happier with tipping.

- Customers like to have control over the compensation. That adds to their satisfaction.

- Servers think that good tips result in good service

- Online rating went down when tipping was removed, maybe in reaction to higher prices. And it rose when tipping was reintroduced.

- Meyer was not able to get the industry to change its practice

The result

According to Meyer, the first December after removing tipping, usually the busiest month, was the best in history. Rating went up by 12 per cent. Applications for kitchen jobs went up 215 per cent. For servers, by 25 per cent. Servers reported no pressure to overreach to get higher tips. Customers also felt that the quality of service was more genuine. Doing the right thing is the most profitable thing. To quote Meyer:

“… there’s a couple things that are hard to measure economically, but they get to the core of why we did this in the first place. The first one – speak to waiters who have undergone this change, and what you hear from them is, even apart from the economics, “I feel better coming to work.” And the two reasons that they have most told us is that they love the fact that there’s just no longer this bubble hanging over their head during the course of your meal where they’re wondering and you’re wondering, “Is the only reason I’m being nice to this guy so I can pick his pocket at the end of the meal?” They love getting rid of that. They love the dynamic that suggests that they’re doing it because they are a hospitality professional. And that feels really, really good to them.

The other thing that our servers love is that they don’t have to feel guilty at the end of an incredibly busy Friday or Saturday night, when they’re all high-fiving, but only behind closed doors because they don’t want the kitchen staff, who only worked harder for the exact same amount of money, to feel bad about it. So everybody just kind of emotionally is loving the fact that we can be transparent.”

Tipping in India

Tipping in India does not seem to have received much attention of researchers. It might have entered India during British rule and tourism over the years. Initially, it probably started off as a rounding off of the amount payable.

In Madras, autorickshaw drivers demand charges above the meter. While writing this, it dawned on me that this could be the legacy of the horse carriage days from the British era. Perhaps there lies a clue to why Uber and Ola drivers insist on cash payments, which are more likely to be rounded off, than tips getting added in digital transfers.

I have had a mix of tipping-related experiences in India. At a popular vegetarian joint near the Madurai temple, a delay in tipping caused the server to tap the saucer a few times, and rather hard, leaving no doubt as to the message. At another vegetarian restaurant in Chennai, where one could expect chartered accountants and other professionals as servers (they claimed so), there were suggestions of tipping or forgetting to give the change, even when service charge was already added.

A New Delhi restaurant added service charge to the bill. As per universal practice, this means that no tipping is expected. But, the payment was collected by the restaurant manager. The change would be brought back by the server who would be purposefully lurking around until you left. But, such creative attempts at having the best of both worlds are rare.

In the Indian Coffee House (ICH) restaurants in Kerala, servers do not collect payment. The customers were required to make payment at the counter. So, no tips. No hanging around near the counter either. But, the experience at ICH outlets in Bengaluru and New Delhi were different despite pathetic quality, service, and ambience.

Tipping and bribes

This brings me back to the initial question of correlating corruption with tipping practices in a country. For those who can afford it, tipping is an easy decision. Tip and be done with it. But, there are social and political costs if the tipping culture is also linked to bribing. A politician who approved the construction of five floors above the approved limit may legitimise bribes as payments towards running his office, his party, his campaign, compensating his supporters, and greasing other palms in the ecosystem.

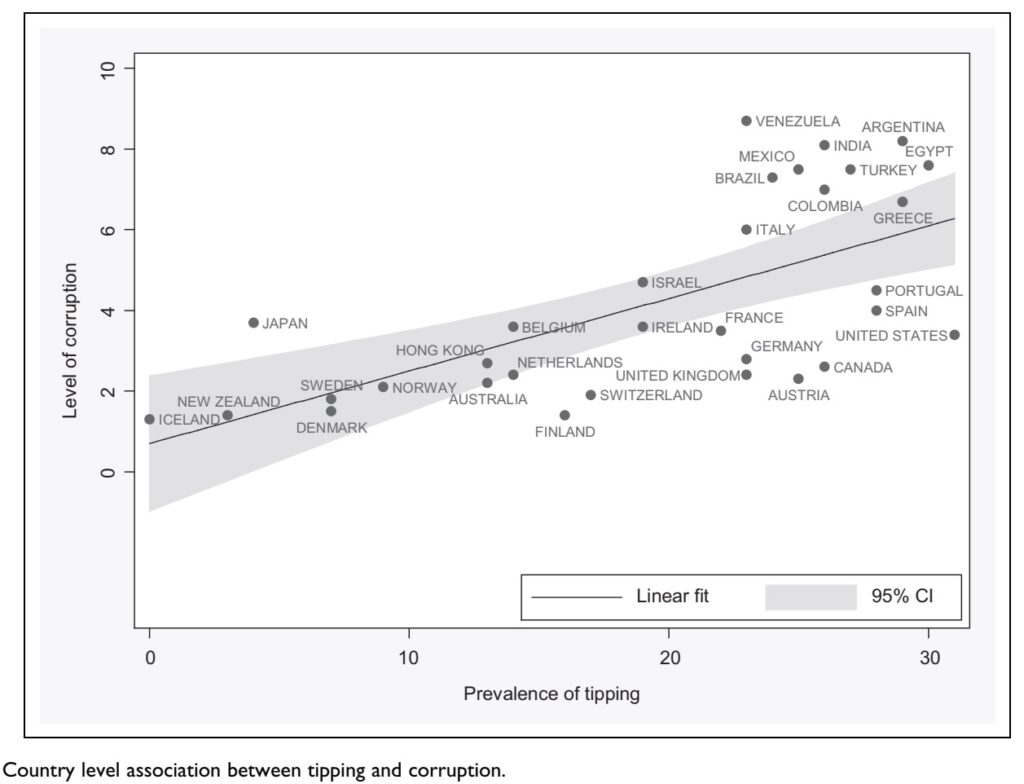

Torfason et al., using archival data for 32 countries, found a positive relationship between tipping and bribery, even after allowing for differences in per capita GDP, income inequality, etc. In other words, countries with higher tipping behaviour tended to have higher corruption. For tipping, they used information from the International Guide on Tipping (Star, 1988) and for bribes, they used Transparency International’s corruption perception index. The tipping levels were calculated as the number of services or professions which involved tipping. The US with 31 had the highest. There were 26 or 27 in Canada and India. Denmark was between five and ten, Japan at four, and Iceland at zero.

They suggest that both tips and bribes come from similar norms of exchange even though many would perceive them as diametrically opposed from a moral point of view. One distinguishing feature is the timing. Bribes usually come before, and tips after the service. They further explain that “the link between tips and bribes appears primarily for those whose tipping is motivated by a prospective orientation (to obtain advantageous service in the future), not for those who have a retrospective orientation (to reward advantageous service in the past).”

Canada and India

You would have noticed an apparent anomaly in the case of Canada and India. They seemingly have the same level of tipping as per the methodology adopted in the study. But, Canada has much lower levels of corruption, 2.9 as against India’s 8.1 (at that time). In 2021, Canada was in the 13th position with a score of 74 while India was at 85 with a score of 40.

The authors suspect that despite similar tipping levels, “Indians are more inclined than Canadians to tip prospectively, that is, in the hope that a tip will bring about better service in the future. We suggest that this prospective orientation can account for cross-national differences in their attitudes toward bribery.”

The last word on this pernicious link between bribery and tipping has not been said. But, I feel that tackling visible, and seemingly less dangerous practices such as tipping, is an essential step towards dealing with bribery and corruption.

Emerging practices

No tipping

Restaurants seem to be increasingly and consciously adopting a no-tipping policy. This is even seen as a point of differentiation from their competitors, and to be on par with other industries where compensation is on merit and not left to the vagaries of customer moods and munificence. Such a policy also avoids discrimination across categories of servers. Towards this end, some restaurants give extra money left by customers on the table to charity. They also announce this a priori to prevent discrimination.

Cash, please

Tipping is entering sectors it was not present earlier. The trades, as well as their trade journals, seem to be promoting it. For instance, even gig workers attached to Uber and Ola are expecting tips. Their apps now provide pre-calibrated tipping options. The workers, on their part, increasingly insist on cash payments where there are chances of payments being rounded off unlike in digital payments.

Tipping vs service charge

To dispense with tipping, restaurants need to add service charges. This may be indicated a priori and stated simply as H.I. or Hospitality Included. The service charge is invariably pooled among a larger number of employees, including the more skilled kitchen workers.

Meyer’s initiative found that eliminating tipping reduced online ratings. The effect was stronger when automatic service charges rather than service-inclusive pricing replaced tipping. The finding that service is better with tipping reinforces the conclusion that tipping improves service as compared to no-tipping.

However, in a Freakonomics podcast (Dubner 2016), Meyer described how everyone was happier after the move to no-tipping in one of his restaurants. He could increase the wages of the back-of-the-house (kitchen) workers and avoid lowering the servers’ wages. There is no free lunch: that is, you cannot charge customers the same amount, increase the salaries of kitchen workers, and have the servers earn the same as before. Someone bears the cost.

Going forward

Tipping is controversial across the world and will probably remain so for a long time. Many countries are debating. For instance, should Australia and New Zealand follow the United States’ example and formally embrace tipping? Are European establishments erring by introducing fixed gratuities?

Instead of just banning tips, minimum wages need to be enforced so that restaurants go for service charges. This will be a legitimate way of charging server time devoted to a table. What better way to calculate than as a percentage of the total bill? It is a better approximation than, say, the time spent.

As the world is still trying to sort out the tipping question, see how Chaplin finally manages to pay his bill and also leave a tip for a particularly obnoxious and demanding waiter as Edna Purviance, his wife soon to be, looks on.

Select references:

Azar, Ofer H. The Economics of Tipping, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2020. Also earlier papers by Azar (2002, 2009).

Chandar, Kneezy, List, and Muir, 2019, The Drivers of Social Preferences: Evidence from a Nationwide Tipping Field Experiment, NBER.

Lynn, 2001, Restaurant Service and Tipping.

Lynn, 2006, Tipping in restaurants around the world.

Torfason et al., Here is a Tip: Prosocial Gratuities are Linked to Corruption, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2012.

Videbeck, 2004, The economics and etiquette of tipping.

Podcasts:

© G. Sreekumar 2022

![]()

Interesting article. The differences between tipping and bribing :

A bribe is demanded by the receiver – tipping is voluntary and entirely at the option of the giver.

A bribe is either given or negotiated before a task is performed – tipping is done after a task done well – never demanded by the recipient.

Tipping is almost always done for lower end income workers – waiters, housekeepers, cab drivers etc. It incentivizes them to do their job well, and to be pleasant and efficient.

Service charges, raising prices etc is not an alternative to tipping. With small businesses in India – I cannot be sure if it will reach the intended worker. Also all workers will get the same amount – whereas I would like to tip only the good ones.

I am all for tipping – and giving some happiness to such workers for making my life comfortable and pleasant !